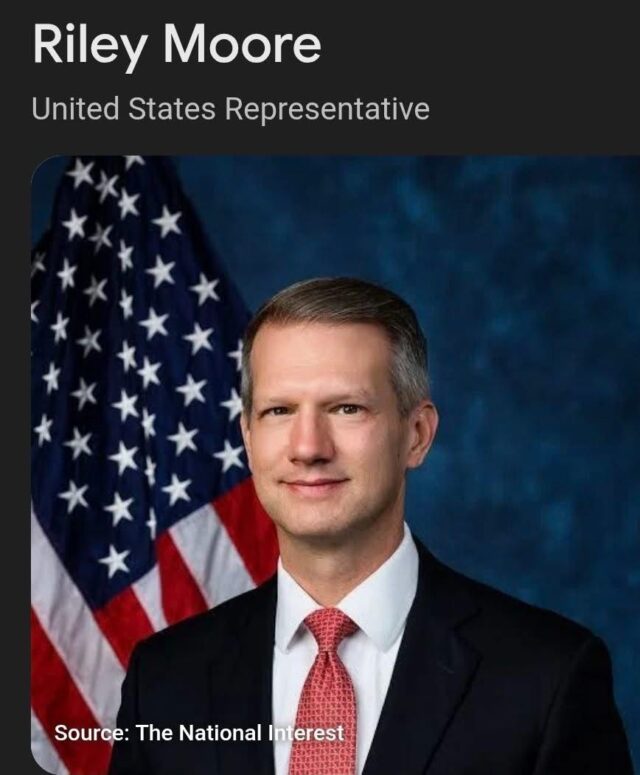

U.S. Congressman Riley Moore has publicly rejected recent claims that the United States is planning to divide Nigeria, a statement made after his high-level meetings in the West African nation. “The discussion of dividing the country never came up,” Moore clarified, addressing allegations that have circulated online. This denial sits at the heart of a complex historical and political issue rooted in Nigeria’s past civil war and ongoing regional tensions. An examination of current U.S. diplomatic efforts and long-standing strategic interests reveals a policy framework focused on partnership and stability, not division.

The Historical Legacy of Biafra:

To understand the sensitivity of these claims, one must look to Nigeria’s history. The Republic of Biafra was a secessionist state that declared independence from Nigeria in May 1967. Its territory consisted of the former Eastern Region, predominantly inhabited by the Igbo ethnic group.

Roots of Secession: The declaration followed a period of intense ethnic violence, including anti-Igbo pogroms in Northern Nigeria in 1966 that killed thousands and caused over a million refugees to flee to the east. The Eastern Region’s leadership concluded that security could only be guaranteed through sovereignty.

A Devastating War: The resulting Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970) was brutal. A Nigerian naval, air and land blockade led to a severe famine, causing an estimated 500,000 to 3 million Biafran civilian deaths, primarily from starvation. The war ended with Biafra’s surrender and reintegration, but the legacy of suffering fuels ongoing Igbo nationalism and secessionist sentiment.

Current U.S. Policy: Partnership Over Division:

Recent official U.S. engagements with Nigeria contradict any agenda of division, instead emphasizing cooperation and respect for sovereignty of Nigeria.

Official Denials and Focus: Mr. Moore, addressing the claims, suggested that destabilizing Nigeria would ultimately empower terrorist groups operating in the region. This aligns with broader U.S. policy that views a unified, stable Nigeria as a strategic partner.

Structured Diplomatic Engagement: The U.S. and Nigeria have established formal channels to address shared concerns. In January 2026, they convened the first session of a U.S.-Nigeria Joint Working Group focused on religious freedom and security.

Core Principle: Both governments reiterated a “strong and unflinching commitment” to “upholding the principles of… sovereignty”.

Stated Goal: The group aims to “create a conducive atmosphere for all Nigerians” and “strengthen counter-terrorism cooperation,” objectives aligned with national unity.

A Broader Strategic Relationship: Analysis from institutions like the Atlantic Council frames the U.S.-Nigeria relationship as one of the most consequential in Africa, anchored by bilateral trade worth approximately $13 billion and deep security cooperation. Nigeria is Africa’s largest economy and most populous country, making its stability a paramount interest for international partners.

Contrasting Views and Persistent Tensions:

Despite official positions, the narrative of external interest in Nigeria’s division persists, often fueled by internal grievances and selective interpretations of foreign statements.

Political Rhetoric vs. Policy: Statements from some U.S. political figures have at times been cited as evidence of interventionist desires. For example, former President Donald Trump has threatened to “go into that now disgraced country” if the government failed to protect Christians from terrorist groups. The Nigerian government has rejected the premise of such claims, asserting its commitment to religious tolerance. However, experts note that such rhetoric, while not reflecting formal policy, can be seized upon by various actors to support their own narratives.

Enduring Grievances: The core issues that led to the Biafran war—including ethnic marginalization, resource control, and questions of federalism—remain unresolved in Nigerian politics. Neo-Biafran secessionist groups like the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) continue to mobilize, often pointing to a history of injustice. This internal strife provides a backdrop against which any foreign comment is intensely scrutinized.

In conclusion, the available evidence from official diplomatic channels and analyses of strategic interest strongly indicates that the United States is not pursuing a policy to divide Nigeria or sponsor a new Biafra. The historical trauma of the civil war makes Nigeria exceptionally sensitive to such claims. Current U.S. engagement, as demonstrated through the Joint Working Group and broader partnership, is formally structured around supporting Nigeria’s sovereignty and internal stability. The persistent rumors of division are more a reflection of Nigeria’s own unresolved internal tensions and the potent legacy of its history than a reflection of current American foreign policy objectives. The path forward for the U.S.-Nigeria relationship, as suggested by policy experts, likely lies in evolving “next-generation engagement” that deepens economic, security, and cultural ties without impinging on Nigeria’s territorial integrity.